Go to Whole Earth Collection Index

by Robert Horvitz, recorded 26 August 2018

RH: Fabrice, I'm trying to break the habit of starting these interviews by asking people how they got involved with Whole Earth, even though that's such a natural beginning. But in your case I really don't know how you got involved, so could you explain?

FF: Well, I was always a big fan of the Whole Earth Catalog, ever since I saw it, way back when I was a teenager growing up in Geneva. As soon as the first Catalog was published, I got hold of it in Switzerland. And when I saw that motto "Access to Tools and Ideas" I said to myself, I've got to be part of this movement. I loved what Stewart Brand was writing. So when I got to the United States, I was actually on my way to India. I was just going to stop quickly in California and then continue on to India. But when I arrived in the United States, I was so fascinated by the culture - particularly the Whole Earth culture - that I decided to stay a few more weeks. Which turned into months and that turned into years. I didn't get to India until 30 years later.

RH: When did you come to the US?

FF: I arrived in California in 1975 and looked Stewart up in the next year or so. Then I became a radio producer, working with the New Dimensions Foundation.

RH: Oh, really? That brings back memories.

FF: Yeah, they were the only group that would take a scraggly teenager as an intern, and I made my way up from the mailing room to producing shows at KPFA and KQED. And as soon as I could, I started interviewing Stewart, whenever I had a radio program that was covering a topic that he was involved in. Actually I would often pick topics that let him say something, just to get more of his wisdom out to the public. Like when he got serious about space colonies, I thought that was a fascinating concept so I did a series of programs on the general topic of life in space and sought Stewart's insights whenever I could, even if it was just a soundbite.

So I started with radio programs, then started a television production company called Videowest, which represented the worldview of the rock generation. When we were 20-somethings there was nothing on TV for us. So I thought, the hell with that, we'll create our own shows that cater to our interests. It was "television for the rest of us." We combined news, music and comedy in a fast-paced magazine format. People said we were like Rolling Stone for the airwaves, and Stewart was often featured in the news segments.

RH: How did you get it out? Were you broadcasting or on cable?

FF: We started on public access cable, then we went to the local UHF station, channel 26, sandwiched in between the Korean and Chinese programming. Then we got a big break: we got on KQED and we suggested to them that they should put us on right before "Saturday Night Live".

RH: Wow.

FF: And from there we got deals with the ABC owned-and-operated stations around the country, to put us on right before "Fridays," which was a clone of "Saturday Night Live." So before we knew it, we were all over the place. We ended up doing the news for MTV during their first few years, all their field news. We had bureaus in New York, LA, Chicago, even London. People would pitch story ideas to us and we would get them shot in the field, send the tape back to San Francisco for editing then send it off to MTV. And as we were growing, people took notice. Kevin Kelly realized that the Next Whole Earth Catalog would need a video section, so he asked if I would edit it. So I selected books and tools for people who wanted to produce video.

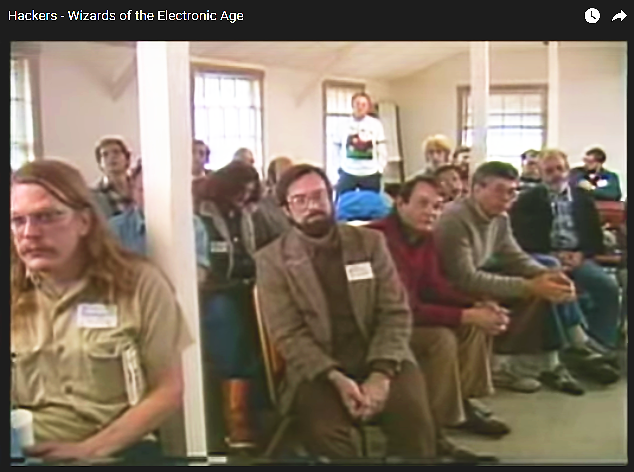

Then Stewart and Kevin got inspired by Steven Levy's book, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, and decided to create the first Hackers Conference in October 1984 - to bring together, for the first time, several generations of computer programmers and hardware designers who made the personal computer revolution possible. They contacted me to ask if I would like to document this event. I was very excited so I said, yeah, absolutely, I'll do it. And they arranged for Steve Wozniak to give us a bit of seed funding so I could hire a camera crew and then I spent almost a year of my life editing the footage. I partnered with KQED, who gave me the editing facilities. I spent alot of time on the editing because I thought it was historically important content. We got some amazing insights from these guys who were, as Stewart says in the video, really sweet, kind and smart. They had alot to say and some of the debates that we captured then still go on today. For example, the tension between information wanting to be free and wanting to be valuable. Questions about whether it's okay for someone to go into the software code authored by someone else and change it. It was a really interesting opportunity to get the word out about a revolution that was just starting to transform our lives.

Through that event I got to know the designers of the Macintosh, Bill Atkinson, Andy Hertzfeld, and some of the other guys, and stayed in touch with them. Bill Atkinson in particular, during the interview that I did with him, was describing software that he would love to see happen, where you could discover nodes of information and jump from one node to another, be able to learn in intuitive and associative ways. It was really fascinating. So I kept in touch and eventually told him hey, I was so inspired by your ideas that I'd like to propose working together. Would it be possible for your Macintoshes to drive some kind of video or multimedia repositories so that people could discover the world through a cross between Powers of Ten and Family of Man? So you'd be able to circumnavigate the globe, zoom down to any place you wanted to see, discover the creatures and cultures that inhabit it. I sketched out the entire concept in great detail, with diagrams, and when he saw it, he flipped because he was writing a piece of software that was perfect for doing this. It was later to be called Hypercard. And so he invited me to come to his home. I was the third person after John Scully and Mike Markkula to take the software home. I was not a programmer, I was a video guy, and suddenly I had this opportunity to create interactive multimedia. I just grabbed the bull by the horns and went for it. I built this whole project, the Interactive Atlas of the World, and then Apple decided to take it inside. I remember getting permission from them to show it to Stewart and Kevin a few years later. It was under nondisclosure, it was top secret, and I invited them to my home so I could show them Hypercard and they were very wowed. It led them to want to create a Hypercard edition of the Whole Earth Software Catalog - to which I contributed as well. And we've stayed in touch ever since. We enjoyed working together. It was a relationship of mutual respect. I'm friends with alot of Whole Earth alumni. Howard Rheingold and I have been making art together for a long time.

RH: Do you have pretty shoes?

FF: I've got pretty shoes that he painted for me. We started the Pataphysical Studios together. Pataphysics is the science of imaginary solutions. It was founded by Alfred Jarry at the turn of the 19th century. It was an early precursor to the Dada and Surrealist movements. We created the Pataphysical Slot Machine, which is a poetic oracle where you sit down in a giant throne, in front of this amazing contraption, and there's a little character in front of you called Ubu and he can read your mind. You think about your life and future and if you want a little bit of advice you press a big button and he gives you a pithy sentence like "embrace purple sky" or something like that, and you're invited to open one of the many "wonderboxes" in front of you, these mysterious Cabinets of Curiosity. You open one of the boxes and it's filled with an artful scene. It could be an Eagle God that comes in and out of a temple, it could be singing flowers, all sorts of beautiful luminescent works created by artists in our community. So we're doing things like that which I call "Maker Art" and we're teaching Maker Art to school children and adults, showing them how they can create their own magical worlds, to help illuminate their lives. Now we're building a Time Machine. It should be ready in a couple of years.

RH: A couple of years ago, you mean?

FF: [Laughs] It was a big mistake that we didn't build it first, but we didn't think of that. These days I'm also very involved in politics, as an artist and activist. We've been creating floats that we take to various parades and rallies. One of them had a tiny Trump and a big Statue of Liberty. Tiny Trump keeps tweeting fake news and every time he does Lady Liberty bops him on the head. It's very popular. We organise singalongs around that. The last float that we did, for Art for Social Change, has a giant Earth ball about 6 feet wide, that spins around and below it are waving hands that honor and celebrate the one planet that we have and below that are works of art on a carousel that were created by young people, ages 12 to 18, showing their ideas for social change and how we can create a better world. And then in the front, on the podium, we put singers and invite everyone to sing along with old classics. This contraption is towed by a Dragon of Change which Howard designed and we implemented as Pataphysical Studios. The idea is to inspire people through art, music and technology.

In my previous work, when I was at Wikipedia or when I had my own nonprofit news organisation, I discovered to my surprise that it was not enough to inform people, you also have to engage them. You have to inspire them. And so alot of the work that we're doing now is focussed on inspiring people to dream - and dream big - and to act on their dreams. Sure, information is absolutely essential and I will always continue to encourage people to find factual information. I devoted seven years of my life to doing that with NewsTrust, which was a guide to good journalism where we encouraged people to help each other evaluate the news that we consume every day. Many of us don't recognise the difference between an opinion and factual reporting. So I spent seven years of my life doing that, then 4 or 5 years at Wikipedia creating tools to help the editors produce information articles and collaborate more effectively with each other.

By the way, Wikipedia has alot in common with the Whole Earth Catalog. Even though it's not a direct descendent, it's a manifestation of the same kind of thinking. I remember talking with Stewart about this. We were both shaking our heading saying there's no way it could possibly work and yet it does! Even if there are issues here and there, it's a fantastic tool for sharing knowledge and ideas. In many ways, the Whole Earth Catalog lives on in Wikipedia.

RH: That's an interesting point. They certainly share a need for quality control. The Whole Earth Catalogs were successful not just because they were broad and comprehensive but because their recommendations were reliable. Stewart's standards and judgment set the tone for everyone's reviews. What made Wikipedia a success is not that anyone can edit the texts but that what's kept online is generally reliable.

FF: Right, a few guiding principles go a long way.

RH: Fabrice, that might be a good ending, your point about Wikipedia and Wikimedia continuing the Whole Earth tradition. Do you have anything else you want to add?

FF: Just that in this new chapter of our lives both Howard and I are now looking at art as a way to engage people's hearts, and once you've done that, then you can bring in the factual stuff. When I teach Maker Art to 5th and 6th graders, they are so enamored with building Cities of the Future, they get so passionate about it that all the factual learning they might otherwise resist happens naturally. They learn everything that they need to learn because their passion is fueling the learning. One of the greatest aspects of Whole Earth culture is that it basically empowered people to go out and try so many things. Even if the ideas are wild and crazy and maybe not all of them pan out, at least we had a chance to experiment and innovate and see what works. And some of the ideas stick. In many ways I think that's the greatest value of Whole Earth's contribution.

RH: Do you want to say anything about this project you're working on for the Catalog's 50th anniversary?

FF: What we're going to do is a retrospective of images, sounds and videos that trace the history of the Whole Earth culture, from the original concepts to the first Catalogs, the people that produced them, and some of the tools and ideas that were presented. We'll follow through with some of the publications that came out of it, CoEvolution Quarterly, the Software Review, etc. We'll have a little bit of video from that first hackers conference. And my hope is that we can end by showing examples of people who were inspired by Whole Earth, and who went on to do great things because of that inspiration. An obvious candidate is Steve Jobs, who mentioned the Whole Earth Catalog as an important inspiration for him and the designers of the Macintosh. They changed the world. We will try to honor what we accomplished together in 50 years, honor the contributors and the unsung heroes working in the offices - along with the "sung heroes" like Stewart. If anyone who is reading this prior to the event has photos or videos or even sounds that reflect the evolution of this movement, they should contact me as I'm very interested in hearing from them.